#Rethinking

A project by Cristina Calderoni, Chiara Campanile, Paula Flores, Denise Parizek

Loredana Manfrè, MicroCollection, Susanna Ravelli, Laure Keyrouz

online: Delilah Gutman, Iryna Shuvalova

artistic residency at Laure Keyrouz art Gallery

Via del Solstizio, 62, 31040 Nervesa della Battaglia (TV)

Italy

from 14th to 17th Septermper, 2024

Performative Installation, Exhibition, Talk, Movie Screening, Poetry,

Music, Symposium hosted by Laure Keyrouz Arts Gallery

Inaugurazione del Giardino della Pace, nuovo luogo del belsentire

Il 16 settembre 2024 alle 5:30 sarà messa in posa la targa “Luogo del Belsentire” presso il Giardino della Pace di

Nervesa della Battaglia, che entra a far parte del progetto “Luoghi del Belsentire”. Il progetto mira a

valorizzare i luoghi italiani in virtù del loro aspetto acustico.

Dettagli sul luogo

Comune di Nervesa della Battaglia (TV)

Ripensando i luoghi…assisti agli eventi culturali di “#rethinking”!

Dal 14 al 17 settembre 2024 si terranno eventi di arte performativa, esibizioni, dibattiti e molto altro del progetto “#rethinking”. La sede dell’associazione RADICA ospiterà la curatrice del progetto Denise Parizek e gli artisti Cristina Calderoni, Chiara Campanile, Paula Flores. L’obiettivo di “Rethinking” è di creare un nuovo tipo di monumento, un luogo di pace e di ripensamento, indipendente dallo Stato e dalla nazione.

Inoltre, parteciperanno MicroCollection (di Elisa Bollazzi), Loredana Manfrè, Annalisa Cattani e Susanna Ravelli.

Catalog

Ausgehend von den Materialien und Inhalten der künstlerischen Projekte von Cristina Calderoni, Chiara Campanile und Paula Flores werde ich Massaman-Curry mit Erdnüssen und Cozze in Weinsauce kochen und dabei auf die Geschichte der Zutaten, ihre Wirkungsweise und Bedeutung in unserer Zeit des massiven Klimawandels eingehen.

Die Themen, mit denen ich arbeite, basieren auf unserer Forschung zu Wurzeln, Kolonialismus, Nachhaltigkeit, Zusammengehörigkeit und Feminismus, wir werden ein Ritual im Garten gestalten. In ihrer „Geschichte eines Gegen-Denkmals“ beschreibt Patrizia Violi die Idee, bestehende Orte/Denkmäler aus ihrem Kontext herauszunehmen und sie durch kollektive Intervention neu zu interpretieren und zu gestalten.

Wie können wir etwas, das uns an den Tod erinnert, eine lebendige Bedeutung geben?

Vom lateinischen ager (Feld, Gebiet, Dorf, Tal…) abgeleitet, ist die Landwirtschaft

nicht nur die Kunst, Felder zu bewirtschaften, sondern auch unsere Kultur selbst. In der lokalen Dimension ist das Gewebe, das sie webt, mit Dialekten, Festen und Mythen verbunden, der Gemeinschaft und der umgebenden Natur verbunden und bildet das Fundament, Fundamente, die den Rest der Komplexität von den frühesten sozialen und politischen Aktivitäten. Die Förderung von agrarkulturellen Veranstaltungen ist nicht nur ein Instrument für die Entwicklung eines bewussten Tourismus, sondern auch eine treibendeKraft für die Gemeinden, sich wieder mit den einzigartigen historischen Wurzeln, Traditionen, die oft schnell verschwinden, und für die Erkundung neuer Praktiken der Verbindung mit der Umwelt. RADICA verwebt agrarkulturelle Initiativen

mit Kunst-, Bildungs- und Freizeitveranstaltungen, um folgende Formen zu erforschen

Formen der Verbindung von Gemeinschaft und Umwelt, alte und neue lokale Traditionen, die Förderung von Praktiken in Randgebieten und aufstrebenden kleinen Gemeinden, neue Formen des nachhaltigen Tourismus.

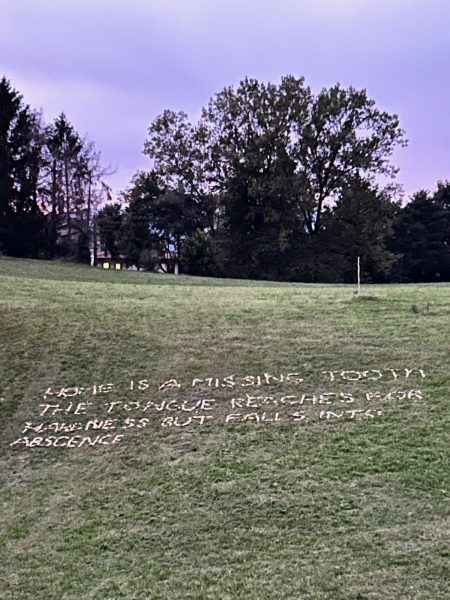

Unser Ziel ist es, eine neue Art von Denkmal zu schaffen, einen Ort des Friedens und

des Umdenkens, unabhängig von Staat und Nation.

Based on the materials and contents of the artistic projects by Cristina Calderoni, Chiara Campanile and Paula Flores, I will cook Massaman curry with peanuts and cozze in wine sauce, and in doing so I will go into the history of the ingredients, their mode of action and significance in our time of massive climate change.

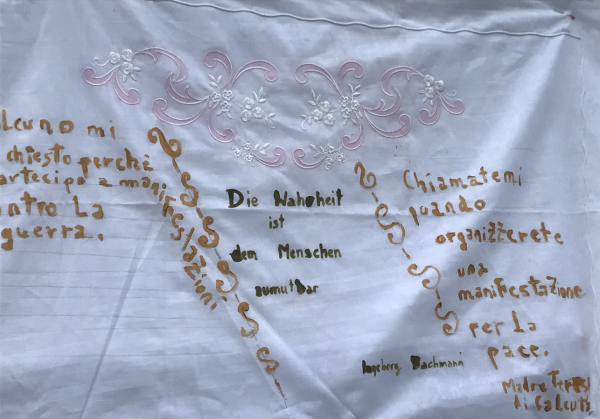

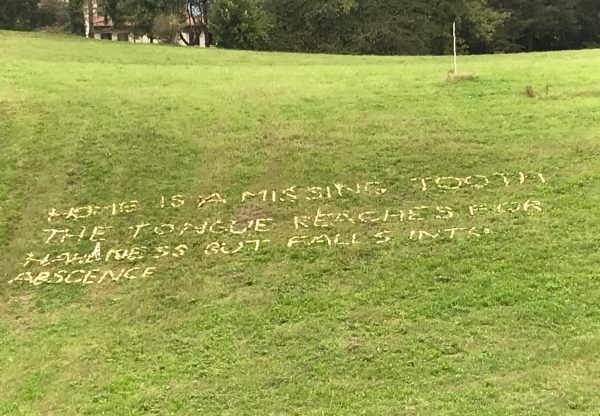

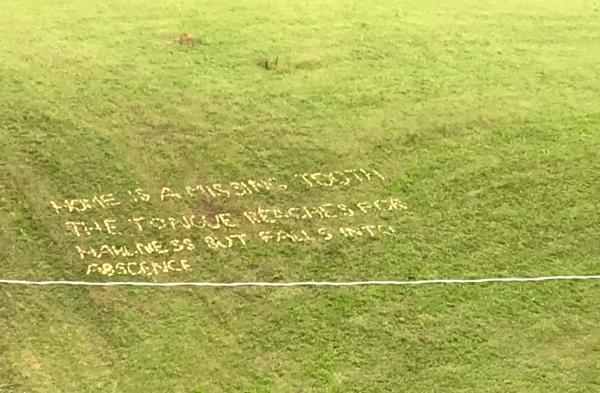

The topics I am working with are based on our research on roots, colonialism, sustainability, togetherness and feminism, we will create a ritual in the garden. In her ‘History of a Counter Monument’, Patrizia Violi describes the idea of taking existing places/monuments out of their context and reinterpreting and redesigning them through collective intervention.

How can we give a living meaning to something that reminds us of

death?

From the Latin ager (field, territory, village, valley…), agriculture is not only the art of cultivating fields, but our culture itself. In the local dimension, the fabric it weaves is linked to dialects, festivals, myths, the community and the surrounding nature, forming the foundations that support the rest of the complexity from the earliest social and political activity. The promotion of agri-cultural events is not only a tool for the development of conscious tourism, but also a driving

force for communities to reconnect with the unique historical roots of the territory they belong to, with traditions that are often fast disappearing, and for the exploration of new practices of connection with the environment. RADICA interweaves agri’cultural initiatives with artistic, educational and recreational events to explore: forms of community and environmental connection, old and new local traditions, supporting practices of marginal areas and emerging small communities, new forms of sustainable tourism.

Our aim is to create a new kind of monument, a place of peace and

rethinking, independent of state and nation. Based on our research on roots, colonialism, sustainability, togetherness and feminism, we will create a ritual in the garden.

In her ‘History of a Counter-Monument’, Patrizia Violi describes the idea of taking existing places/monuments out of their context and reinterpreting and redesigning them through collective intervention.

How can we give a living meaning to something that reminds us of death?

Partendo dai materiali e dai contenuti dei progetti artistici di Cristina Calderoni, Chiara Campanile e Paula Flores, cucinerò il Massaman curry con arachidi e cozze in salsa di vino, approfondendo la storia degli ingredienti, le loro modalità di azione e il loro significato nel nostro tempo di massicci cambiamenti climatici.

I temi su cui sto lavorando si basano sulla nostra ricerca sulle radici, il colonialismo, la sostenibilità, l’unione e il femminismo, e creeremo un rituale in giardino. Nel suo “Storia di un contro-monumento”, Patrizia Violi descrive l’idea di estrarre luoghi/monumenti esistenti dal loro contesto e di reinterpretarli e riprogettarli attraverso un intervento collettivo.

Come possiamo dare un significato vivo a qualcosa che ci ricorda la morte?

Dal latino ager (campo, territorio, villaggio, valle…), l’agricoltura non è solo l’arte di coltivare i campi, ma la nostra stessa cultura.

Nella dimensione locale, il tessuto che essa tesse è legato ai dialetti, alle feste, ai miti, alla comunità e alla natura circostante, costituendo le fondamenta che sostengono il resto della complessità fin dalle prime attività sociali e politiche. La promozione di eventi agri-culturali non è solo uno strumento per lo sviluppo di un turismo consapevole, ma anche un volano per le comunità per riconnettersi con le radici storiche uniche del territorio di appartenenza, con tradizioni che spesso stanno rapidamente scomparendo, e per l’esplorazione di nuove pratiche di connessione con l’ambiente. RADICA intreccia iniziative agro-culturali con eventi artistici, educativi e ricreativi per esplorare: forme di connessione comunitaria e ambientale, vecchie e nuove tradizioni locali, pratiche di sostegno delle aree marginali e delle piccole comunità emergenti, nuove forme di turismo sostenibile.

Il nostro obiettivo è creare un nuovo tipo di monumento, un luogo di pace e di ripensamento, indipendente dallo Stato e dalla nazione.

Sulla base della nostra ricerca sulle radici, il colonialismo, la sostenibilità, l’unione e il femminismo, creeremo un rituale nel giardino.

Nella sua “Storia di un contro-monumento”, Patrizia Violi descrive l’idea di estrarre luoghi/monumenti esistenti dal loro contesto e di reinterpretarli e riprogettarli attraverso un intervento collettivo.

Come possiamo dare un significato vivo a qualcosa che ci ricorda la morte?

Denise Parizek Curator

Pictures of the exhibition

Photocredits by Cristina Calderoni, Paula Flores, Mute Insurgent

24 hours

eggs, flour, baking soda, water

This action was created during the art residency in Ihla do Mel, Brazil. It is an invitation to a dinner where the food is an edible sculpture. Convivio is a collective body and the dish is a traditional recipe from my family. A gesture that activates poetry and proposes the materialisation of an encounter.

CHIARA CAMPANILE Artist

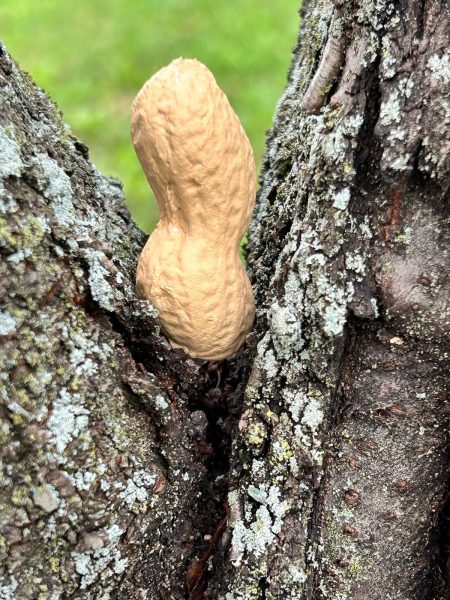

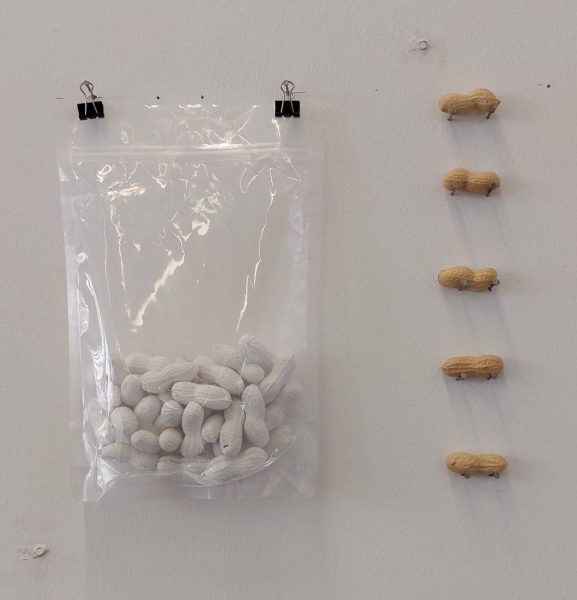

It’s not peanut butter

“work for peanuts” or “if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys”, it means to work for very little money, or that if you pay little, you get unskilled workers. I’m fascinated by the use of idioms in languages because they are created by the collective intelligence and contain an indirect way of describing its way of thinking. In the English language, peanuts are considered something small, a negligible amount, something not very significant, and are always referred to as a plurality. To focus attention on only one characteristic of this bean-like nut, its size, necessarily leaves out others. Peanuts are seeds and multipliers of life that grow hidden in the ground. The yellow flower bends and hides beneath the earth, where the seeds can grow in the privacy of the earth’s womb. Quite a shy plant in my opinion! These are all aspects that are often overlooked as humans often focus on the utility of nature and what we can eat or use to our advantage. In this work I’m presenting a series of realistic, life-size sculptures of peanuts. I like to strip this seed of its usefulness to focus on the idea of it itself rather than its use, to learn together to look at it with different eyes.

Non è burro di arachidi

“work for peanuts”(lavorare per le noccioline), o “if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys” (se paghi le noccioline avrai scimmie), significa lavorare per pochi soldi, o che se paghi poco avrai lavoratori non qualificati. Mi affascina l’uso dei modi di dire nelle lingue perché sono creati dall’intelligenza collettiva e contengono un modo indiretto di descrivere il suo modo di pensare. Nella lingua inglese peanuts è considerato qualcosa di piccolo, una quantità trascurabile, qualcosa di poco significativo e viene sempre indicato come una pluralità. La scelta di concentrare l’attenzione su una sola caratteristica di questa noce simile a un fagiolo, la sua dimensione, ne tralascia necessariamente altre. Le arachidi sono semi e sono propagatori di vita che crescono nascosti nel terreno. Il fiore giallo si piega e si nasconde sotto la terra dove i semi possono crescere nell’intimità del grembo della terra. Una pianta piuttosto timida, a mio parere! Sono tutti aspetti che spesso vengono trascurati perché l’uomo si concentra spesso sull’utilità della natura e su ciò che possiamo mangiare o usare a nostro vantaggio. In questo lavoro presento una serie di sculture realistiche e di dimensioni reali di arachidi. Mi piace spogliare questo seme della sua utilità per concentrarmi sull’idea stessa del seme piuttosto che sul suo utilizzo, per imparare insieme a guardarlo con occhi diversi.

Mussels (cozze) are a carbon sink. Studies based on farmed bivalve shellfish show that they are excellent carbon dioxide sequestrators. This makes them a full circle on benefits for Carbon dioxide sequestration by keeping it in their shells as insoluble and indigestible calcium carbonate, they produce food which is high in protein and they can also be used to improve soil conditions in agriculture. They also improve the quality of the water by filtering different organic and inorganic compounds from heavy metals to excess nutrients and algae among others.

Organisms sequester CO₂ at different quantities and rates. Some are more efficient than others. Some produce or consume more than what their body can sequester.

Now that there is a rush and a market to sequester CO₂, organisms are given a value worth for the CO₂ sequestration capacity.

The risk with this is that organisms become more or less valuable depending on how much they can serve us and serve our needs for the manipulation of the environment.

Le cozze sono un serbatoio di carbonio. Studi basati su molluschi bivalvi di allevamento dimostrano che sono eccellenti sequestratori di anidride carbonica. Questo fa sì che le cozze siano un vero e proprio circolo virtuoso per il sequestro dell’anidride carbonica, in quanto la trattengono nelle loro conchiglie sotto forma di carbonato di calcio insolubile e indigeribile, producono cibo ad alto contenuto proteico e possono anche essere utilizzate per migliorare le condizioni del suolo in agricoltura. Migliorano anche la qualità dell’acqua filtrando diversi composti organici e inorganici, dai metalli pesanti ai nutrienti in eccesso e alle alghe.

Gli organismi sequestrano la CO₂ in quantità e tassi diversi. Alcuni sono più efficienti di altri. Alcuni producono o consumano più di quanto il loro organismo possa sequestrare.

Ora che c’è una corsa e un mercato al sequestro di CO₂, agli organismi viene attribuito un valore per la capacità di sequestro di CO₂.

Il rischio è che gli organismi diventino più o meno preziosi a seconda di quanto possano servire a noi e alle nostre esigenze di manipolazione dell’ambiente.

DENISE PARIZEK Curator

Arachidi e Cozze

Arachidi / peanuts are probably originated in Brazil and Peru. As long as South American natives are doing pottery, they used the shape of peanuts or decorated the pottery with it. Tribes in central Brazil also ground peanuts with maize to make an intoxicating beverage for celebrations. Peanuts were grown as far north as Mexico by the time the Spanish began their exploration of the new world. The explorers took peanuts back to Spain, where they are still grown. In Europe they used it as pig for in the beginning. From Spain trades and explorers took peanuts to Africa and Asia. In Africa the plant became common in the western tropical region and was regarded by many Africans as one of the several plants possessing a soul. With African Slaves the peanuts were brought to North America. Slaves planted peanuts through out the southern USA. Since 1800 peanuts were grown commercially in South Carolina and were used for oil, food and substituted for cacao. Originally they were regarded as food for the poor, but after starting the Civil War in 1860, there was a notable increase of peanuts consumption, especially under soldiers.

Gorge Washington Carver, a former slave freed at the age of 4 years and the first African American faculty member at an university (University of Iowa), discovered and publishes from 1896 on, the importance of peanuts. He found out that peanuts are able to restore nutrients to the soil, most notable nitrogen, which is a main ingredient in modern fertilizers. Peanuts are also naturally resistent to many pests and diseases that are running rampant across the South. The protein, was badly needed in the diets of many Southerners. In 1916 Carver published “How to crow the peanuts and 105 ways of preparing it for human consumption”. Within the next 50 years, peanuts would become the second most produced crop in the South of the USA. Carver was also proponent f sustainable agriculture, livestock care and education. He encouraged farmer to submit samples of their soil and water and visited local farmers to teach modern agriculture and food preservation techniques.

Peanuts are no nuts, they are legume, related to beans, lentils or soy.

They are rich in protein, high in various vitamins (diverse B complexes like B1, B3, B9), Vitamin E and minerals like phosphorus, copper, manganese and magnesium. They are fat, but have a very low glycemic index, good for people with diabetes and are reducing risks of heart disesases.

Cozze / mussels also have a long history dating back to ancient times. The earliest records of cozy consumption can be traced to indigenous communities of North America and Europe. Even the Romans farmed cozze. Native Americans along the Pacific Northwest Cost included mussels a a staple in their diets, smoked or dried for preservation.Mussels are among the first marine organisms to be cultivated by humans. They are relatively easy to grow and have many uses. They were also used as fertiliser and fish bait.

They filter up to 2 litres of seawater per hour and are the sewage treatment plants of the oceans. They live mainly in intertidal and shelf areas, but smaller groups also live highly symbiotically with chemotrophic bacteria in the deep sea at hydrothermal vents with methane seepage. Some species can live to a very old age; Crenomytilus grayanus has been recorded to be over 126 years old.

Global shipping has enabled them to spread as far as South Africa, where they have become an invasive species that poses a threat to native mussels.

Mussels are protein bombs and rich in omega 3 fatty acids, which have an anti-inflammatory effect and have a positive impact on brain development. They are also rich in vitamins A, C and E and B complexes. They also contain the minerals calcium, magnesium, phosphate, iron and fluoride.

Arachidi and Cozze both have a long tradition that has had and continues to have a global impact. The two foods are of great importance in both agriculture and fishing, mutating from simple food for the poor to today’s sophisticated dietary requirements. The ingredients of peanuts and mussels are similar, have an antioxidant effect and are good for the heart and brain.

Due to the pollution of the oceans, the health factor of mussels can be questioned today, as they retain a lot of pollutants by filtering the seawater.

They are also a good example of the distribution of food before the era of globalisation and of the adaptation and use of foreign plants and animals.

Le arachidi sono probabilmente originarie del Brasile e del Perù. Finché gli indigeni sudamericani hanno lavorato la ceramica, hanno usato la forma delle arachidi o hanno decorato la ceramica con esse. Le tribù del Brasile centrale hanno anche macinato le arachidi con il mais per ottenere una bevanda inebriante per le celebrazioni. Le arachidi venivano coltivate fino al Messico, quando gli spagnoli iniziarono l’esplorazione del nuovo mondo. Gli esploratori portarono le arachidi in Spagna, dove vengono ancora coltivate. In Europa, all’inizio, le usavano come alimento per i maiali. Dalla Spagna i commerci e gli esploratori portarono le arachidi in Africa e in Asia. In Africa la pianta divenne comune nella regione tropicale occidentale e fu considerata da molti africani come una delle numerose piante dotate di anima. Con gli schiavi africani le arachidi furono portate in Nord America. Gli schiavi piantarono arachidi in tutto il sud degli Stati Uniti. Dal 1800 le arachidi sono state coltivate a livello commerciale nella Carolina del Sud e sono state utilizzate per l’olio, per l’alimentazione e come sostituto del cacao. In origine erano considerate un alimento per i poveri, ma dopo l’inizio della Guerra Civile nel 1860, ci fu un notevole aumento del consumo di arachidi, soprattutto tra i soldati. Gorge Washington Carver, ex schiavo liberato all’età di 4 anni e primo membro afroamericano della facoltà universitaria (Università dell’Iowa), scoprì e pubblicò a partire dal 1896 l’importanza delle arachidi. Scoprì che le arachidi sono in grado di restituire al terreno le sostanze nutritive, soprattutto l’azoto, ingrediente principale dei moderni fertilizzanti. Le arachidi sono anche naturalmente resistenti a molti parassiti e malattie che dilagano nel Sud. Le proteine erano molto necessarie nella dieta di molti abitanti del Sud. Nel 1916 Carver pubblicò “Come affollare le arachidi e 105 modi di prepararle per il consumo umano”. Nei 50 anni successivi, le arachidi sarebbero diventate la seconda coltura più prodotta nel Sud degli Stati Uniti. Carver era anche un sostenitore dell’agricoltura sostenibile, della cura del bestiame e dell’educazione. Incoraggiò gli agricoltori a presentare campioni del loro terreno e dell’acqua e visitò gli agricoltori locali per insegnare le moderne tecniche di agricoltura e conservazione degli alimenti. Le arachidi non sono noci, ma legumi, parenti di fagioli, lenticchie o soia.

Sono ricche di proteine, di varie vitamine (diversi complessi B come B1, B3, B9), di vitamina E e di minerali come fosforo, rame, manganese e magnesio. Sono grassi, ma hanno un indice glicemico molto basso, ottimo per chi soffre di diabete e riducono il rischio di malattie cardiache.

Anche le cozze hanno una lunga storia che risale ai tempi antichi. Le prime testimonianze del consumo di cozze risalgono alle comunità indigene del Nord America e dell’Europa. Anche i Romani coltivavano le cozze. I nativi americani lungo la costa nord-occidentale del Pacifico includevano le cozze nella loro dieta, affumicate o essiccate per la conservazione. Le cozze sono tra i primi organismi marini a essere coltivati dall’uomo. Sono relativamente facili da coltivare e hanno molti usi. Venivano utilizzate anche come fertilizzante e come esca per i pesci. Filtrano fino a 2 litri di acqua marina all’ora e sono gli impianti di depurazione degli oceani. Vivono principalmente nelle zone intertidali e di piattaforma, ma gruppi più piccoli vivono anche in alta simbiosi con batteri chemiotrofi nelle profondità marine, presso le bocche idrotermali con infiltrazioni di metano. Alcune specie possono vivere fino a un’età molto avanzata; il Crenomytilus grayanus ha superato i 126 anni. Il trasporto marittimo globale ne ha permesso la diffusione fino al Sudafrica, dove sono diventate una specie invasiva che rappresenta una minaccia per le cozze autoctone.

Le cozze sono bombe proteiche e ricche di acidi grassi omega 3, che hanno un effetto antinfiammatorio e un impatto positivo sullo sviluppo del cervello. Sono anche ricche di vitamine A, C ed E e di complessi B. Contengono inoltre i minerali calcio, magnesio, fosfato, ferro e fluoro.

Arachidi e Cozze hanno entrambi una lunga tradizione che ha avuto e continua ad avere un impatto globale. I due alimenti hanno una grande importanza sia nell’agricoltura che nella pesca, passando da semplici alimenti per i poveri alle sofisticate esigenze alimentari di oggi.

Gli ingredienti delle arachidi e delle cozze sono simili, hanno un effetto antiossidante e fanno bene al cuore e al cervello.

A causa dell’inquinamento degli oceani, oggi il fattore salute delle cozze può essere messo in discussione, poiché esse trattengono molti inquinanti filtrando l’acqua di mare.

Sono anche un buon esempio della distribuzione del cibo prima dell’era della globalizzazione e dell’adattamento e dell’uso di piante e animali stranieri.

LAURE KEYROUZ Artist, Curator, Host of the Residency

After the video with Andrea Stomeo, ‘A New World’1, my return to Lebanon this summer for three weeks was very important to continue reflecting on how ‘a new world’ could be, despite the challenges of Lebanon’s changed political situation in 2024. In the media, it was believed that all of Lebanon was a war zone, but this was not the case where we were, in Beirut and Marej, in Bsharre. It was a summer of non-stop parties, crowded restaurants, everything twice as expensive as in Italy. This oasis of peace that we have in Marej, with jedo, teta and good people, freshness, art and creativity… My only violent artistic gesture was to cut the frames of my old canvases from an exhibition of mine entitled ‘Più lontano da un sogno’, signed in 2003, to take them to Italy and let them see the light again after being protected and hidden in a corner of a house, standing there since I left Italy in 2005. So, without thinking too much about it, with a Swiss knife I cut the frames and removed the staples from the frame, putting them inside a big potato sack, then inside a big suitcase, and off to the airport without any concern or attention to the artistic heritage, and to the identification of the works as fragile and important to be carefully guarded. Around this sack of potatoes were books in Arabic donated by the ‘Al-Jadid’ publishing house of the Lokman Slim Foundation, where I wrote the word ‘Garden of Peace’ in this sacred place, where his grave is, killed like so many intellectuals for speaking the truth. His sister Racha kept telling me that he lived with the spirits, still mourning his death. Writing ‘سلام’ ‘Peace’ with books. Another suitcase contained plants for herbal teas, zaatar, kechek, the supplies I take every time I go to Lebanon.

These two suitcases form the starting point of a performance in the gallery to talk about unfinished art projects and canvases left in the dark, suspended between one country and another. With two videos, one showing moments spent in Lebanon with children ‘adventurous in nature’, each of whom chose a tree. After I visited and found inspiration in the Valley of Adonis (Nahr Ibrahim)2, Naia, my niece, played the new Astarte, who wakes up in 2024 and sees a changed and polluted world. Other women will be invited to take up this mythology in their lives today. This will be complemented with a performance, painting, installation and artist’s book and linked with a second video work in progress centred on the figure of Mayram, the wife of the famous Shapiro who was part of the artists‘ colony at La Ruche, an artists’ residence in the Montparnasse district. La Ruche (meaning ‘The Beehive’) was an important artistic and cultural centre during the first decades of the 20th century, hosting many emerging artists, including Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine and Marc Chagall. The performance is in collaboration with Silvia Galluccio and Ambra Curato.

Significance: Returning to Lebanon after two years away and following news stories created only to frighten those in the diaspora, falsifying the real image of Lebanon and always painting it as a country of war and conflict. To go beyond the limits is to have the courage to go and see for yourself what is happening. As my sister says, you have to call those who live there and ask. The reality is different. We are in a different country, another Lebanon, where there are signs along the highway saying: ‘We are tired, Lebanon does not want war’. This is the real message. The Lebanese ignore the constant wars and live by closing their ears to bad news. No TV. Sea, mountains, parties and relatives. And after three weeks, defying calls to return early for fear the airport will close, the Turkish Airlines plane is still there. You take with you art old and new, photos and videos to edit, writing, Lebanese food, books and children, and you squeeze through the crowd of people with only Arab planes into Beirut airport, remembering Najwa Barakat’s voice: ما في ولا طيارة اجنبية فيا تحط بمطار بيروت

‘There is no foreign plane that can land at Beirut airport’. Meanwhile, poor Kathy, my brother’s wife, who was supposed to come to Lebanon from Australia with four of her children and meet us there after not seeing her for years, had her flight cancelled, leaving us all in shock after dreaming of the moment of meeting her.

A bottle filled with sea water from Beirut remains in the gallery, at the request of Elisa Bollazzi delivered to her, who presented our project, mine and Angelo Ricciardi’s, entitled Carissimo Angelo, 2016 in which we emptied the sea: me in Beirut and him in Naples. A small video shows the place where the water was collected.’

Dopo il video con Andrea Stomeo, “A New World”1, mio ritorno in Libano quest’estate, per tre settimane, è stato molto importante per continuare a riflettere su come possa essere “un nuovo mondo”, nonostante le sfide della situazione politica del Libano, cambiata nel 2024. Nei media si credeva che tutto il Libano fosse una zona di guerra, ma non era così dove eravamo noi, a Beirut e a Marej, a Bsharre. Era un’estate di feste continue, ristoranti affollati, tutto costoso, il doppio rispetto all’Italia. Quest’oasi di pace che abbiamo a Marej, con jedo, teta e persone buone, freschezza, arte e creatività… L’unico gesto artistico violento mio è stato tagliare le cornici delle mie tele vecchie da una mia mostra intitolata “Più lontano da un sogno”, firmata nel 2003, per portarli in Italia e farli rivedere la luce dopo essere stati protetti e nascosti in un angolo di una casa, fermi lì da quando ho lasciato l’Italia nel 2005. Così, senza pensarci troppo, con un coltello svizzero ho tagliato le cornici e rimosso le graffette del telaio, mettendole dentro un grande sacco di patate, poi dentro una valigia grande, e via in aeroporto senza alcuna preoccupazione o attenzione al patrimonio artistico, e all’identificazione delle opere come fragili e importanti da custodire con cura. Attorno a questo sacco di patate c’erano libri in arabo donati dalla casa editrice “Al-Jadid” della fondazione Lokman Slim, dove ho scritto la parola “Giardino di Pace” in questo luogo sacro, dove c’è la sua tomba, ucciso come tanti intellettuali per aver detto la verità. La sorella Racha continuava a dirmi che viveva con gli spiriti, piangendo ancora sua morte. Verrà proposta la scrittura “سلام” “Pace” con i libri. Un’altra valigia conteneva piante per tisane, zaatar, kechek, il rifornimento che faccio ogni volta che vado in Libano.

Queste due valigie costituiscono il punto di partenza di una performance in galleria per parlare di progetti artistici incompleti e tele rimasti al buio, in sospensione tra un paese e l’altro. Con due video, uno che mostra momenti passati in Libano con bambini “avventurosi nella natura”, ciascuno dei quali ha scelto un albero. Dopo che ho visitato e trovato ispirazione nella Valle di Adone (Nahr Ibrahim)2, Naia, mia nipote, ha interpretato la nuova Astarte, che si sveglia nel 2024 e vede un mondo cambiato e inquinato. Altre donne saranno invitate a riprendere questa mitologia nella vita di oggi. Questo verrà completato con una performance, pittura, installazione e libro d’artista e collegato con un secondo video work in progress centrato sulla figura di Mayram, la moglie del famoso Shapiro che ha fatto parte della colonia di artisti a La Ruche, una residenza per artisti situata nel quartiere di Montparnasse. La Ruche (che significa “L’Alveare”) è stata un importante centro artistico e culturale durante le prime decadi del XX secolo, ospitando molti artisti emergenti, tra cui Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine e Marc Chagall. La performance è in collaborazione con Silvia Galluccio e Ambra Curato.

Significato: Il ritorno in Libano dopo due anni di lontananza e seguire notizie nate solo per impaurire chi è in diaspora, falsificando l’immagine reale del Libano e dipingendolo sempre come un paese di guerra e conflitti. Oltrepassare i limiti è avere il coraggio di andare e vedere di persona cosa succede. Come dice mia sorella, bisogna chiamare chi abita lì e chiedere. La realtà è un’altra. Siamo in un paese diverso, un altro Libano, dove ci sono cartelli lungo l’autostrada che dicono: “Siamo stanchi, il Libano non vuole la guerra”. Questo è il vero messaggio. I libanesi ignorano le guerre continue e vivono chiudendo le orecchie alle brutte notizie. Niente TV. Mare, montagna, feste e parenti. E dopo tre settimane, sfidando le chiamate che chiedono di tornare prima per paura che l’aeroporto chiuda, l’aereo della Turkish Airlines è ancora lì. Si porta con sé arte vecchia e nuova, foto e video da montare, scrittura, cibo libanese, libri e figli, e ci si infila tra la folla di persone con solo aerei arabi nell’aeroporto di Beirut, ricordando la voce di Najwa Barakat: ما في ولا طيارة اجنبية فيا تحط بمطار بيروت

“Non c’è nessun aereo straniero che può atterrare all’aeroporto di Beirut”. Intanto, alla povera Kathy, moglie di mio fratello, che doveva venire in Libano dall’Australia con quattro dei suoi figli e incontrarci lì dopo anni che non la vedevo, hanno cancellato il volo, lasciandoci tutti sotto shock dopo aver sognato il momento dell’incontro con lei.

Rimane in galleria una bottiglia riempita con l’acqua del mare di Beirut, su richiesta di Elisa Bollazzi consegnata in galleria a lei, che ha presentato il nostro progetto, mio e di Angelo Ricciardi, intitolato Carissimo Angelo, 2016 in cui svuotavamo il mare: io a Beirut e lui a Napoli. Un piccolo video mostra il luogo dov’è stata raccolta l’acqua.”

Questa è la seconda tappa, dopo aver scritto un’altra lettera che dovevo mandare a lui, questa lettera non sarà mai mandata in posta ma letta in galleria poi rinchiusa in una bottiglia di vetro per essere mandata attraverso il fiume Piave. Una copia di questa lettera verrà affidata a un amico a Trieste che va in Palestina per gettarla in mare e farla arrivare alla gente sofferente di Gaza, come balsamo per chi la leggerà, per far sapere che l’umanità non è morta e da lui raggiunge il mare da Napoli. Ci sono poeti e artisti che continuano a fare arte e scrivono: “No alla guerra. Sì alla vera pace”.

I lavori d’arte dimostrano che c’è una continuità, come le onde del mare, tra un lavoro e l’altro, e rimangono aperti a un’altra trasformazione e metamorfosi cucendo relazione e reti con le altre donne in residenza per “ripensare” a un nuovo mondo e zona di pace. Come la scritta fatta a Bsharri con il marmo “No War”.

This is the second stage, after having written another letter that I had to send to him, this letter will never be sent by post but read in the gallery then enclosed in a glass bottle to be sent across the river Piave. A copy of this letter will be entrusted to a friend in Trieste who goes to Palestine to throw it into the sea and send it to the suffering people of Gaza, as a balm for those who read it, to let them know that humanity is not dead and it reaches the sea from Naples. There are poets and artists who continue to make art and write: ‘No to war. Yes to true peace’.

The art works show that there is a continuity, like the waves of the sea, between one work and the next, and they remain open to another transformation and metamorphosis by sewing relationships and networks with the other women in residence to ‘rethink’ a new world and zone of peace. Like the inscription made in Bsharri with marble ‘No War’.

LINKS

https://cristinacalderonistudio.com/Convivio

https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/923780640

Supported by